Matt’s Top Ten Reading List

My Five Fiction and Five Nonfiction Essentials

Books are everything to me. That would be an understatement, to say the least. If I were stranded on that all proverbial desert island with no other possessions but food and water I’d be half tempted to trade those preserves for a well-worn paperback book and a pen with which to mark it up at my leisure. So much of my life is centered around books; collecting them, reading them, annotating them, displaying them, loaning them out to friends and family, cultivating a well-kept “To-Read” list and balancing the ever growing stack of “Up Next” texts. These are essential components of my life and I cannot imagine how I’d spend my days without them.

But I could wax poetically about books for hours – I could, indeed, fill a whole book with loving thoughts about books. But that’s not what this tract is for. Rather, I thought it fitting to make the first blog posted on my website be a nod to the incredible authors and minds who have influenced me, entertained me, or just otherwise helped me pass the time between classes or work meetings over the years.

I thought it only fair to split the list between fiction and nonfiction so I hope there’s something here for everyone to find engaging in some capacity. If you’ve never read these works, I highly recommend checking them out! So without further ado…

Top Five Fiction

1) The Great American Novel by Philip Roth

I love baseball almost as much as I love books, even when my cherished New York Yankees insist on accelerating the graying of my hair. So it came as no surprise when an author as talented as Philip Roth managed to suck me into his story of a forgotten – intentionally erased, in fact – third major league which got itself wrapped up with Soviet spies and condemned to the dustbin of history. A fan of baseball history like myself will find no shortage of inside baseball – pun very much intended – references to suit your fancy. Those who aren’t partial to America’s Game will find Roth’s usual whit and colorful characterizations more than entertaining as before long you’ll find yourself wondering why the fictional Mike Masterson doesn’t have a plaque in Cooperstown.

But Roth utilizes baseball, and the colorful characters who occupy its fields, as a microcosm 0f America itself, an examination of a post-war corruption that, in the 1950s, was steadily distorting the idyllic image of the nation. Where Masterson is everything good about America in America’s mind – pious, virtuous, enterprising, humble, and all other matter of flattering epitaphs – he is struck down by the cocky upstart Gil Gamesh, epitomizing Americans attitudes towards international communism. And yet Roth isn’t laughing with McCarthy Era America, nor with similar efforts of forced cognitive conformity that have grown larger and larger since the author’s death in 2018; he’s laughing at them. Any story that can bottle up the battle for America’s soul and package it into a biting satirical epic playing out on the sandlot is always going to end up at the top of my list and, as of writing in August of 2023, it remains far and away my favorite book of all time.

2) Dune by Frank Herbert

I had, admittedly, never read a word of Frank Herbert’s celebrated Dune saga by the time the first trailers for the 2021 movie based on the first novel dropped online. It was those trailers which brought me to explore the series in the first place, and I am certainly glad I did. Over the course of a year from December 2020 to December of 2021 I read all six of the novels penned by Herbert before his death. There is not much to say that hasn’t been said about the works over their many years of circulation. The world is engaging, the characters are unique and compelling; it is an exploration of the nuances and enterprises which set the course of human civilization. It is a masterpiece that will engage both the historian and political scientist for its engaging examination of politics and state building as well as the traditional science fiction fan for which this is the model for much of the modern genre.

But this entry is solely focused on the first novel, Dune, rather than the series. While saying the opening series was easily Herbert’s opus would be breaking no new ground, I think it also fair to say the introduction to the universe of Arrakis is the only one in the series that remains essential reading for any fans of literature as it is easily a classic in its own right, apart from the genre or series in which it is set. Much as Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy – to which the Dune series is often compared – is not merely a work for fantasy fans, Herbert’s work transcends the field of science fiction to stand our as something I don’t believe it has, as of yet, been fairly recognized: a modern piece of the Western Canon.

3) Cain by José Saramago

The first book I ever read by the Nobel Laureate José Saramago was the author’s last and wow, what a way to go out. If ever an aspiring author might want to find themselves feeling utterly inadequate as a writer, they should read the work of Saramago, who often seems capable of saying more in a single sentence than most could hope to express in an entire novel. To say Saramago was a master of his craft would be stating the obvious, and run the risk of being redundant with the amount of praise and awards lavished on the Portuguese bard during his lifetime. Would-be readers should be ready for a bit of culture shock as Saramago’s unique style largely foregoes the use of proper noun capitalization and substitutes commas in place of most other punctuation.

Following his retelling of man’s fall from Eden, Saramago, an atheist, uses the much maligned Old Testament figure of Cain, the son of Adam and Eve, to explore the incongruities and contradiction of Christian dogma as well as its negative impacts on humanity. One might get the impression that Cain is a stand-in for the author himself, a man who once knew God – or rather, thought he knew God – and now finds himself, older and experienced, looking around and wondering what good God had done for the mess of humanity on earth. For his part God, as portrayed by Saramago in other works such as his controversial Gospel According to Jesus Christ, resembles a deity from the pantheons of Roman, Greek, or Norse mythologies. Far from benevolent, loving, and inherently good, Saramago’s God is petty, covetous, jealous, bitter, and mercurial. Cain, as well as Saramago, is angry at the world of God, and angry at his fellow man for continuing to worship such a being. Reading along, one can’t help but be angry with them.

4) I, Claudius/Claudius the God by Robert Graves

Cheating a bit here but these two books can only ever be read in concert, encompassing the full, faux-autobiographic life and reign of the Roman Emperor Claudius, or, as Graves has it, “Poor Claudius”, or “Claw-Claw Claudius” in reference to the deformed statesman’s lifelong stammer. To date, this is the only work I’ve bought a hard copy of after originally listening to it on tape, eager as I was to display the work in a tangible form. It is considered by many to be Graves’s greatest work, ironic since he claimed to have only ever written the initial tale of I, Claudius because he was broke and desperately needed a paycheck.

Few writers are talented enough to make the reader root for an all-powerful, all – conquering godhead of a militaristic state like Rome. Burt Graves’s Claudius – who serves also serves double duty as our narrator - clever, studious, and embattled strikes the audience with an enduring quality one might struggle to properly put into words. But in that mysterious quality lies Claudius’s conniving brilliance, his strategy to stay alive and, ultimately, assume power himself. Graves’s opus, I, Claudius is a tragicomedy of immortal proportions. (As a particularly nerdy side note, I highly recommend reading the short work written by Claudius’s contemporary, Seneca the Younger, Apocolocyntosis Claudii – literally, The Pumpkinification of Claudius. Written a millennia earlier, Seneca’s satire matches Graves’s tone and whit to describe Claudius’s inauspicious adventure to heaven, making this the perfect spiritual conclusion to Grave’s masterwork.)

5) It Can’t Happen Here by Sinclair Lewis

The 2016 Presidential Election marked a critical juncture in modern American history and for those of us younger voters who were casting a ballot for the first time, a critical episode in the shaping of our overall worldview and political identifications. I had just turned 18 in the months before, in that period of time where the prospect of then-Candidate Donald Trump defeating the establishment-darling Hillary Clinton seemed a farfetched fantasy. In those months I acquired a copy of Sinclair Lewis’s It Can’t Happen Here and began to consider whether or not the truisms of American democracy – its vaunted checks and balances, its guardrails against demagogues – might not be so ironclad after all. In those months, I took comfort in the near certainty Lewis had been wrong and the prescient work was merely a coincidence of history. By November, I knew it was I who had been wrong.

Lewis – writing in 1935, during the first rise of fascism in Europe – describes a United States which, unable to find its footing amidst the ongoing Great Depression, finds itself seduced by the grotesque solutions being offered by the likes of Hitler in Germany, Mussolini in Italy, and Franco in Spain. This movement finds its figurehead in the form of a grotesque and ridiculous man with an appropriately silly name: Berzelius “Buzz” Windrip. Windrip sets about attacking minorities, eroding the separation of powers, denouncing journalists, and jailing political opponents. The result is a seemingly unrecognizable United States, one which – both at the time of Lewis’s writing and my reading in 2016 – seemed impossible. In hindsight, Lewis was not so much the carnival fortune teller he once appeared; he instead correctly diagnoses both the threat inherent in a still nascent, yet-to-be fully understood fascist ideology as well as the root causes of such an ideology’s existence in the first place. What makes him all the more ahead of his time – indeed, ahead of many still in our own time – is his willingness to acknowledge the conditions for such a distorted state actively exist in our own society, reminding us a citizenry caught unawares is a citizenry in danger. Lewis’s work is all the greater for its timeless relevance, however terrifying that very relevance may be.

Top Five Non-Fiction

1) These Truths by Jill Lepore

Should I ever have to take an oath of office, rest assured this will be the book I swear upon. Whenever asked, as I often am, which book out of all I’ve read I would deem the most essential, I never hesitate to answer with the name of These Truths by Jill Lepore. Lepore, one of the greatest living American historian, traces the story of the United States from Columbus’s landing in Cuba through to the modern day. With engaging prose and stunning revelations of the painted over pages of American history, Lepore manages to produce perhaps the most comprehensive and definitive history of the United States to date.

While its size may be daunting, Lepore’s exceptional skill as a writer makes it more than digestible, indeed enjoyable, for even someone unaccustomed to pouring over historical accounts. Unlike many historians who choose a 30,000 foot view of events around them, Lepore’s work is critically aware of the times in which it was written in and, indeed, serves as a guidebook for events which created our current world and crises. In an era of great political bewilderment, anyone trying to make sense of it all through a historical analysis, I will not only recommend you start with These Truths, I would insist upon it.

2) Midnight Express by Billy Hayes

Billy Hayes and I were both born and raised on Long Island, but that’s far from the only reason this amazing work will forever rank among my favorite books of all time. In large part due to the success of the Oliver Stone film – complete with Stone’s signature alterations of history – based on Hayes’s book, there are those who forget this cruel, and yet somehow beautiful story, is a true one. In 1970, Hayes was a college student traveling abroad in Turkey – he was, to borrow an overused phrase, trying to find himself. In the process, Hayes took it upon himself to strap four pounds of Turkish hashish to his person before stepping on a flight back to the United States. Discovered, Hayes would be charged with possession and sentenced to just over four years. But, on the eve of his release, looking to make an example of Hayes in an effort to combat drug trafficking by tourists and travelers, the Turkish courts reversed course and sentenced the student to life in prison. The courts would later alter Hayes’s sentence again, reducing it this time to a still devastating 30 years inside some of the most infamous prisons on the planet. Hayes was trapped, thousands of miles away from everything he ever knew – or thought he knew.

What follows is a man’s reflection of life amidst conditions seemingly designed to break the human spirit, and the wisdom learned by being forced to adapt, function, and survive under crippling circumstances. Far from breaking his spirit, Hayes found many of the answers he was looking for behind the walls of prison and underwent a spiritual and personal examination that under normal conditions he may never have been capable of facing. Above all, Midnight Express is a testament to humanity’s will towards freedom, its desire for expression, its struggle – and success – in finding joy where none should otherwise exist. Perhaps it was because Hayes, as the narrator, was the same age I was while reading it, but Midnight Express has never strayed far from the front of my mind. There is, quite unexpectedly, something utterly universal in the lessons learned during a remarkable ordeal.

3) Manufacturing Consent by Noam Chomsky and Edward S. Herman

As someone with a degree in journalism I admit the absence of this book is a glaring gap in the curriculum – and judging from the number of fellow journalists who have never read this essential text, not one unique to my undergraduate program. Incomparable social critics, Chomsky – a political activist – and Herman – an economist – formulate within these pages a seminal theory of modern life: the propaganda model hypothesis. In short, the two demonstrate how the corporate media model – through advertising revenue, snowballing concentration of ownership, and an overreliance on government sources and close access to power – produces an inherent conflict of interest which, far from serving the essential role of informing the people instead works to promote a narrative beneficial to those whose interests can be advanced using their wealth and power. In this system, reporters are reduced from a once-elevated position of trusted truth-tellers to mere stenographers for the powerful.

Chomsky and Herman’s work is all the more pertinent when we realize the issues examined in this text – issues which led, almost directly, to both the Vietnam and Iraq Wars – have only gotten worse since the second edition was published in 2002 on the eve of the Second Bush Administration’s invasion of Iraq. Media ownership has become increasingly centralized, perhaps best exemplified by the purchase of the Washington Post, the paper of record in the nation’s capital, by Jeff Bezos in 2013 and Twitter, among the most popular social network and news sites in the world, by Elon Musk in 2022 – at the respective times of acquisition, both Bezos and Musk were estimated to be the world’s richest individuals. Meanwhile, overall public trust in media institutions continue to plummet. The result is the mess of misinformation and propaganda we find ourselves in today. With no clear solution in sight, more than ever Manufacturing Consent is essential reading not only for reporters in the field but anyone trying to sort through the noise and surmise the truth behind it all.

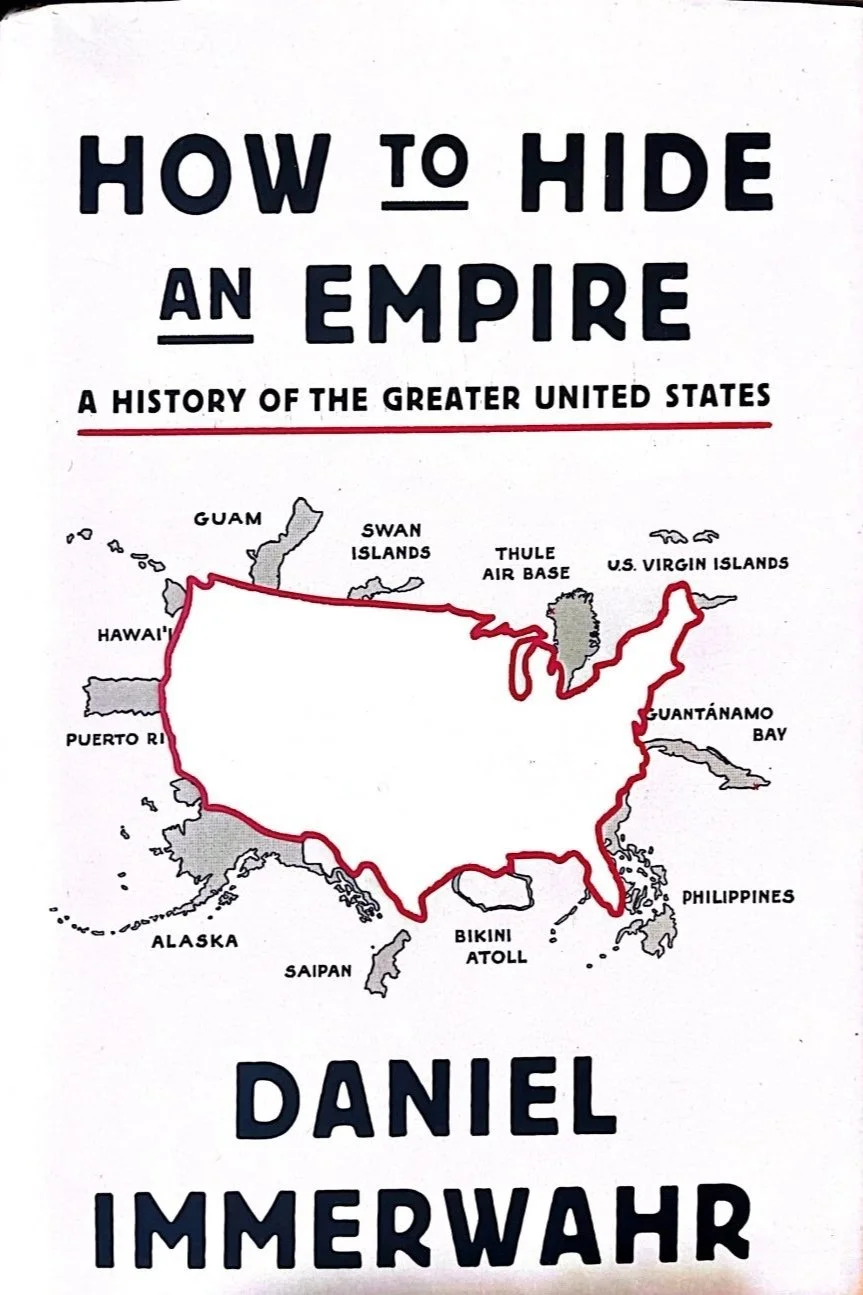

4) How to Hide An Empire by Daniel Immerwahr

It was Napoleon who said, “History is a pack of lies agrees upon.” No sentiment best describes Immerwahr’s excellent dissection of the history of America’s shadowy global empire. Immerwahr begins his story at the empire’s zenith – 1945, the fall of fascism in Europe and the end of World War II. With Europe and Asia in utter ruin, the United States, he describes, looked out at the world and saw a beaten land ripe for conquest. For thousands of years, various empire would have jumped at the opportunity to unite an old Roman ideal and bring all the world under its yoke. But in this moment the United States chose otherwise – the rightful conquerors of the West gave the West back. For nearly a century mainstream historians have described America’s history with empire as one of antagonism, only ever embracing its excesses unwillingly, and even then temporarily. The United States, these historians say, did not impose a post-war military rule over the world because of its principled groundings in freedom and self-determination.

Immerwahr argues differently: the United States did dominate the postwar world. But instead of doing so in a manner resembling the old colonial empires of England and France, the United States could afford to shepherd affairs from a distance – wielding the control over post-war financial systems in one hand and an advanced military force, complete with the world’s largest military budget (by far) in the other. Rather than plant flags in the soil of the Global South, Immerwahr writes, American interests planted military bases, business investments, and stop signs. And America’s relationship to empire didn’t merely begin in the ruins of Europe. Immerwahr guides the reader through the story of America as it happened to the people of the Cherokee and Sioux Nations, to the people of the Kingdom of Hawai’i, of Puerto Rico, Cuba, and of the Philippines. Theirs are stories not told in American public schools, not spoken of on national holidays, not given blockbuster films starring A-List celebrities. But they are key elements of America’s history and grappling with them is essential to not only understanding America’s past but its inevitable future. Immerwahr’s fantastic book is a terrific and essential starting point for doing just that.

5) The Histories by Herodotus

The only reason The Histories, the original masterwork of history, is not higher on this portion of the list is because it truly straddles the line between fact and fiction, and to masterful effect. Not for nothing is its author, the ancient Greek Herodotus, known as both the “Father of History” and the “Father of Lies.” As the world’s first travel writer, Herodotus never traveled to many of the far off lands he describes, relying instead on hearsay; as its first historian he was never one to let the truth get in the way of a good story, interweaving ledger and legend, fact and fiction. It is unlikely, yet poetically human, that this paradoxical individual would become the definitive source for of the ancient West’s most important moments: the Greco-Persian War. If you’ve seen Zach Snyder’s overly stylized movie, 300, you know the most important bits: the Persians under King Xerxes invades Greece, the divided Greeks fall prey to the huge Persian army, Sparta refuses to surrender and, with just 300 soldiers, hold back the invading forces long enough to inspire all of Greece to rise like David against Goliath, saving Greek civilization from their conquering neighbors.

But this is only part of Herodotus’s story. The Histories crisscrosses the ancient world to delight even the modern audience with stories of love and death, of tribes of men with dog heads in India and Africa, of people with faces on their chest and no heads, of Queens, Kings, philosophers, heroes, fools, and gods, of Amazon warriors and Athenian democracy. It even includes the oldest ever recorded reference of cannabis use, as Herodotus describes how the ancient Scythians on the Black Sea would burn the marijuana leaves in sauna-like room and absorb the fumes to experience mild-altering effects – what anyone familiar with modern weed culture would readily identify as “hot- boxing.” As a historian and a lover of history there is no better companion than Herodotus. More relevant to the casual reader, the ancient Greek is remarkably modern in his human, striking in his prose, and always reread able. Whether your first read or your tenth, one could never go wrong with opening the Histories to a random page and read on – you’re bound to find something in there to enjoy. For thousands of years’ worth of greatness, Herodotus will always be among my Must-Reads.